Much of the following essay comes after reflecting on my reading of Oscar Wilde, William Blake, Harold Bloom, Northrop Frye, and probably Roger Scruton.1 I thank them—frankly, I am not sure where their thoughts end and my thoughts begin.

Introduction: The Aim of This Essay

Discourse on the imagination, I think, is lacking. At least, there is not much talk of the imagination as I come to appreciate and understand it. The three realms of explicative work on the imagination are:

Philosophy - usually not engaging with the imagination on its own terms, instead trying to explain how we imagine things that aren’t there—usually as an exercise to see how far one’s own epistemological foundations can go.

Science - particularly the science of creativity. Focused not on the images of the imagination or its deeper meanings, but instead focused on neurological processes and the contexts in which those processes are exhibited.

Mysticism/New Age - A self-help aberration, interested less in the imagination and more in the outcomes which it brings. These are the radical utilitarians.

These three, while useful within their own disciplines, do not, I think, attempt to describe the imagination’s true importance. Something is missing—a certain romanticism, a certain “for-it’s-own-sake”, which is usurped by moralism and utilitarian anxiety—but we will get to that later.

For now, let us begin with the imagination’s primary domain—the domain where we, human beings, can fully express the world in our heads: Art.

1. Art proper

Art is the use of the imagination to produce beauty.

What we call the most beautiful are the representations that most inspire our imagination—and art is the realm of the beautiful. Consider the statue Venus de Milo:

Now, there are certain wrong ways to perceive this statue. If one uses history as the primary means of analysis2, it’s safe to say that one is looking at the statue in a wrong way—at least if appreciation and exploration of the artistic imagination is concerned.

In our (post-?) postmodern age, we have (regrettably) taken “the interest of different, contradictory perspectives” to mean “the conflict between systems of power”.

The question is then: what is the right way?

Again, take a look at Venus. Yes, there are narratives of power and history and whatever else, but open yourself up to the beauty of the statue’s portrayal.

Immediately striking is the ideal form of the goddess—or at least, what the artist thought the ideal was! In a sense, the statue is a question from the artist to the viewer: “Can’t you see how beautiful it is?”

Now, beauty can’t be argued—the limitation the critic always brushes up against. One can only hope that other agrees with one’s own experience of beauty. If there is no agreement, there’s nothing more to say.

“Interesting perspective, but I disagree”. Welcome to the land of idiosyncrasies3.

2. Art Explored Further

In a sense, Venus de Milo exists only in our minds. Before me stands a mere piece of marble, objectively with no more meaning than anything else surrounding it. Moreover, the actual statue is itself an imperfect symbol. I mean—if it wasn’t obvious—she has no arms, and there’s a chip below her left breast.

In the depiction of the goddess Venus, the statue is a failure! There is no movement, no pulse, no voice. It is a statue.

She is a statue because Venus cannot be realized. The statue is merely a suggestion. However, actually, it’s exactly in this space of suggestion that art derives its power. This gap is where we appreciate a masterful work, this gap is the love of beauty, art, and the imagination—precisely in its unrealizability and imperfection.

In art, there are two main things happening.

The perception of something merely beautiful,

The suggestion of something infinitely more beautiful to the imagination.

Only in the appreciation of this duo can art be truly admired.

We look at the Venus de Milo and think “If only she could move!”

The gap between what is shown and what is suggested is agonizing—an unvaultable gap that eternally traumatizes us. The more we are suggested, the more we are traumatized.

What is suggested is our own ideals. Within the minds of every man is the unrealized dream world. A place of true freedom—unlimited time, unlimited wants, & unlimited means. The “real” Venus de Milo presides within this world. She walks in the stone-carved streets picking orchids in the nourishing Roman sun. In looking at the statue, we are reminded of her presence there which we have cluelessly forgotten.

What is suggested by art is its own reality. Here’s what I mean: imagine if the statue became real and walked and talked before our eyes in this real world. Contrary to, perhaps, our first impression, this would be a tragedy. Why? Because Venus de Milo would now be merely a part of our vulgar, oozing, violating world—into the world that doesn’t “hold itself together”. If she can be made real, then she is ripped from our ideal. When seeing a painting, we do not wish the painting to spread out into our world and claim a section of our world as its own. We want to jump into the painting. If the artwork becomes a part of our own reality, it goes into the category of what can be accomplished, and what can be accomplished is not what we hold dear. It’s the impossible that has us dreaming.

The aesthetic suggestion is that the work in question points to our ultimate reality—you, for a moment, are an inhabitant in the world that the work has created—a world more real, more meaningful, more tactile than the one we live in day-to-day.

Interlude

We walk around in life with the dreadful feeling that “something is wrong”.

Our birth violently removes us from the quiet completeness of the womb. As a result, we toil endlessly to rediscover that sense of belonging and warmth for the rest of our life, and even when we get it, there is still something missing—we soon realize that we will never return to that fluid, self-contained bliss.

We continue living, and as we do, our idealism is challenged again and again by the ordinary disappointments of life—the cold, the boredom; we are attacked, cheated, and lied to in every crevice. Everyone else is a stranger, their motives ambiguous, and we sulk into an ever-retreating corner of the world that we built for our own self-insulation.

Even the beginning of your days are small synecdoches of the tragedy of life: every morning we are torn from the sweet abyss of sleep into the groggy, ambulatory realness of being awake.

Then, one day, we decide to go to a museum. It’s been a while since you’ve gone, after all. And look, you’re in Paris, the artistic center of human history, with the greatest art museum of all: The Louvre.

You remember that the Mona Lisa is there, considered to be history’s greatest piece of art. You, of course, never understood this fact. Surely, the crowds that it brings are pure convention, nothing but fake enthusiasm for a random painting of a random woman. But hey, you’re in Paris! Why not go? Just to see. Once.

You go. There’s a huge line. You can barely make out the outline of the face, too many people. You wait and stand, each time getting closer, the fragments of your vision getting more complete until you are at the front of the line. You look at it straight on, finally, face to face:

3. What is Art?

Threefold: Art is the representation of our internal structures (imagination), mediated by our forms of expression, and perceived by our senses.

Representation of Our Internal Structures

There is the way of the world and there is the way of our mind. The way of the world, to us, is lonely, alien, and absurd, but only because we have an ideal of “how things should be” inside of us.

We perceive the world and understand it to a fair degree, but we do not want it. Our lives are a mess—full of false starts and stops, nothing going on as planned, and our sense of security is slowly undermined. As children, we look to the old for guidance on the confusing world which we accept, but the old’s authority does not last forever—eventually, the reservoir dries up. A novel situation meets an inexperienced individual, and we realize that we are truly, and irrevocably severed.

As Hemmingway says:

The world breaks everyone and afterward many are strong at the broken places. But those that will not break it kills. It kills the very good and the very gentle and the very brave impartially. If you are none of these you can be sure it will kill you too but there will be no special hurry.

- A Farewell to Arms 1929, Ernest Hemmingway

This is not how it is supposed to go!

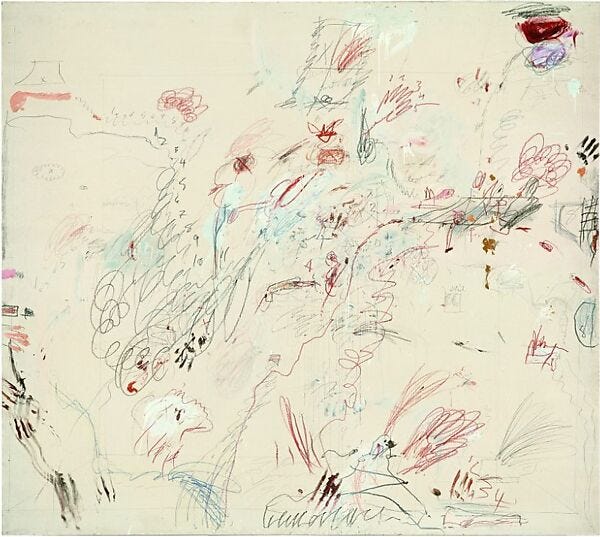

Inside of us is a desire for wholeness, for belonging. This is the structure internal to us, filled with understandable human symbols and meanings. We constantly attempt, usually in vain, to realize this yearning, to build the Meaningful World we can understand under no uncertainty. Art is the attempt (again: in vain) to bridge this gap, and this is the case with even the most abstract art. Take the following works by Rothko and Cy Twombly, artists usually ridiculed for their obtuseness and lack of meaning:

Surely, this is, in a sense, a replication of nature, is it not? With it’s uneventful, pretentious, chaotic silence.

I argue: No. There is something to be seen here, just not in terms of the real world but in the imaginative world. In the Rothko or Twombly, we do not see the structure of logic or abstraction, but something radically different. There isn’t even a pretext or intention to portray symbols or themes: it’s pure human expression with no commitments. Only here are you truly free.

As such, the response one has to these works is equally non-descript and sensual. These works require from you nothing, they are a refuge from the world of obligation and limitation. These abstracts are attempts to show the imagination as purely as it can. Nowhere will you find such assemblages of color and mark—it gives a message tailored to the human being in only a way he can make sense of.

Look at the Rothko; is there not something fundamentally beautiful in the compactness of the rectangles? It’s a message of “home”, so simple and bare that it is almost terrifying.

Twombly’s is another matter; a callback to energy and pure mental material. This is the world of the child marking the page with no care— a world we all inhabited.

Look closer, but not in an attempt at “below-the-surface” moral or utilitarian meaning—rather, stick to the surface and see the marks and colors as events happening in the world of imagination.

Mediated by Our Forms and Perceived by Our Senses

Art is not a product of contemplation. One does not think up a beautiful work or solve an artistic problem as one does a math equation. Only through our imagination interacting with pre-existing forms of expression do we create a work of art.

All of our technologies follow the following pattern (this includes language, the telephone, the wheel, etc.):

Discovery

Use for Practical Purposes

Exhaustion of practical purposes (i.e. we’ve used it to solve as many real-world problems as the technology allows)

Use for art

In this final step, the technology seems to have a life of its own, but really it’s our own life, our own interiority, that is finally living. Technology insulates us from the worries of survival and the battle with nature, and now we can finally tap into the well of creativity. The final step is infinite—we never reach the ‘end’ of the poem, painting, or song, and mediums forever change by the addition of the novel tool.

What results are art movements, styles, and fashions, each one critiquing the past while also paying its due. The result is endless novelty and rediscovery.

4. Today

If my views on artistic imagination are correct, or even worthy of consideration as an ideal, what are we to make of contemporary American culture?

This is a country of pragmatism. The national morality is “Form follows function” in virtually every avenue of life. One is to fill their days with “productive” activity, with no outlet or even interest in those deeper parts of us. Material and career goods are the aspirations while the imaginative, emotional, and artistic are paid lip service, though beneath the superficial smile is the disdain and “well, that simply won’t work!” presumption. Unlike our Western counterparts—the Europeans—art in the United States primarily developed to support advertising and commercial entertainment. There, they use the imagination only as far as it brings more material goods into their arms. The cost is a lack of culture & belonging, with a pervading ugliness countered by the lower-order idealisms of partisanship, ideology, and fundamentalism.

Of course, there have been very bright American moments of artistic merit, but they were mere moments within a landscape worried more about moral prescription and self-replication.

Instead of beauty, the young pursue fame and power, while the old pursue nothing.

But no! I will stop here, lest this end up as a polemic!

Conclusion

Before you was my account of the imagination as a structure within ourselves that puts an understandable, belonging, beautiful order to the alien, lonely, and cold world. Our main tool for the expression of this world is the, alas! imperfect Art. Despite its imperfection, it suggests a world much more real and tactile than the one we spend most of our time in.

Our lives are more enriched the more we expose ourselves to good art and our imagination. What we call painting, music, literature, religion, politics, mysticism, and the entire host of things we cling onto dearly to make sense of ourselves, others, and the world is in fact pointing to one sublime, beautiful unreality, which we avoid to our own spiritual, bodily, and mental peril.

Read, listen, see—go to the endless reservoir of meaning and belonging—drink from the cauldron of experience—there, men are your brothers, women your sisters, and nature with a voice that you can understand.

So go! Grab hold of the gold in your soul!

Also: Slavoj Žižek, Martin Buber, James P. Carse—there are others.

Or class struggle, the physical properties of the marble, even the minute criticisms of proportion.

That’s isn’t to say that the perception of beauty is static. One can learn to find something beautiful. One can learn to receive the beauty in the previously seemingly unbeautiful message.